Newspapers vs. newsletters: how the world of information is changing

Every decline is always accompanied by a parallel rise in something else: this was true for music, when cassettes gave rise to CDs first and then Spotify, and more recently for video entertainment, with the crisis of generalist television and the success of Netflix and other similar platforms. Today we could also apply the same scheme to the world of information: the gradual decline of newspapers is witnessing the rise of new tools for disseminating, transmitting and retrieving information, first and foremost newsletters.

So why do we speak of “revival”? Because in reality newsletters have always been a crucial tool for attracting the public and conveying information, and their birth was historically well before traditional newspapers. The Acta Diurna (“daily events”) was published in 131 BC and was the first newsletter in history, a gazette containing military and political news for public dissemination (1). Newsletters have never stopped circulating since then, crossing the various historical periods (2) with different forms and purposes and today, more than 2,000 years later, we are witnessing a whole new life of this information channel.

How the epidemic has changed the world of information

The beginning of the traditional media crisis

It was 2007 when two apparently insignificant events represented the beginning of the crisis in the traditional world of information:

- the boom of Facebook

- the presentation of the first iPhone

These are the two historical facts that gradually led to the crisis of the traditional information world and to a new way of transmitting, retrieving, and disseminating news, in which:

- the narration of reality has gone from being the absolute prerogative of traditional media to being produced and disseminated by users themselves. Smartphones and social networks have made news literally at hand, and news stories can be told and transmitted by anyone

- newspapers began to lose exclusive control of the spread of news and their role as the sole sources of information

- the methods for finding news moved to digital, becoming much faster and more immediate. The web has given users the opportunity to find out news in real time, making timeliness a need that the printed word will never be able to satisfy.

The crisis of printed newspapers reached significant dimensions within a decade, even before the Covid pandemic, with dramatic effects for the journalism job market.

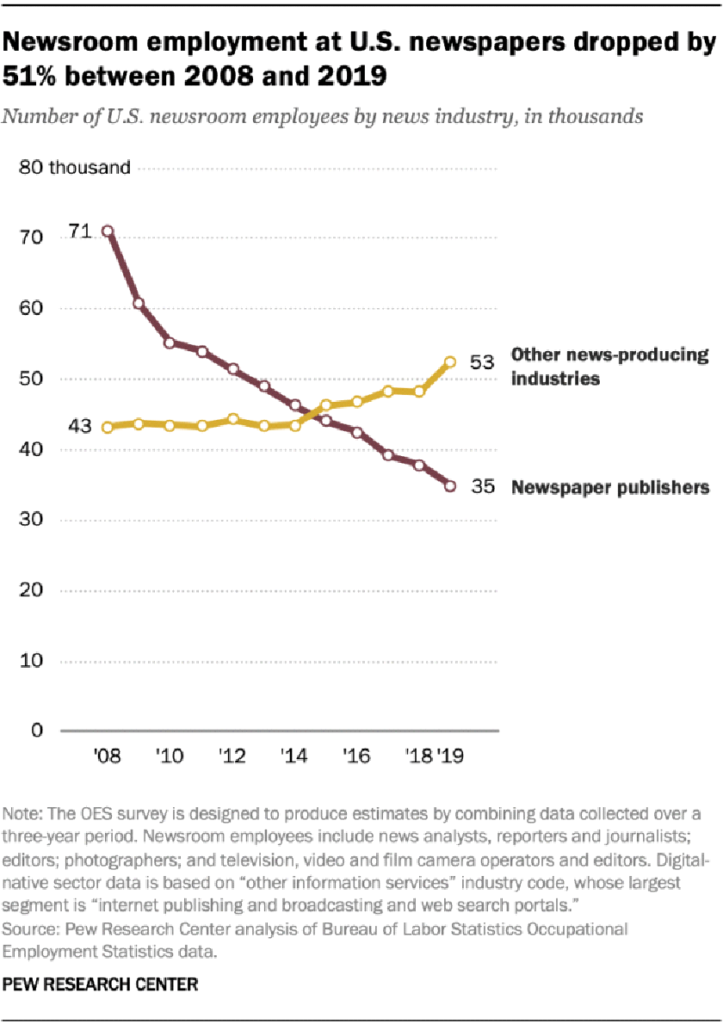

According to the Pew Research Center, in the American scenario alone, the printing industry lost half of its employees from 2008 to 2019:

How the epidemic accelerated the newspaper crisis

Given these premises, in a historical context where the survival of newspapers was already hanging on a thread, the Covid pandemic not only accelerated a process of digitization, but also the decline of printed news along with it: in America, the signs of the newspaper crisis first manifested themselves with a widespread and dramatic increase in permits, strikes and layoffs, up to the closure of more than 60 local newspapers. In June 2020, the Financial Times 2020 reported 38,000 layoffs and pay cuts in the printing industry. With a 40% loss in advertising revenue since the start of the pandemic in June 2020, the Minneapolis Star Tribune is just one of many victims of a now evident global crisis. In other cases, the decline in revenue has reached 90%, forcing a large number of newspapers to rely exclusively on readers’ subscriptions to survive.

The rise of newsletters

The success of Substack and newsletter subscription services

It is within this scenario that many journalists are seeking alternative solutions to overcome the crisis and survive. One of these is undoubtedly Substack, a platform created in 2017 that offers any company or journalist the ability to create and send newsletters to their subscribers, asking readers for money for the subscription and funding. In only a few years Substack has launched a real service model for the subscription and consultation of free or paid newsletters (at the author’s discretion).

The post announcing the platform’s launch (4) not only indicates Substack’s mission, but also a sort of manifesto of the current world of information:

“The great journalistic totems of the last century are dying. News organizations—and other entities that masquerade as them—are turning to increasingly desperate measures for survival. And so we have content farms, clickbait, listicles, inane but viral debates over optical illusions, and a “fake news” epidemic. Just as damaging is that, in the eyes of consumers, journalistic content has lost much of its perceived value—especially as measured in dollars. It’s easy to feel discouraged by these dire developments, but in every crisis there is opportunity. We believe that journalistic content has intrinsic value and that it doesn’t have to be given away for free. We believe that what you read matters. And we believe that there has never been a better time to bolster and protect those ideals.”

In the first three months of the pandemic, Substack increased its revenue by 60% and the number of readers and authors doubled. The Dispatch is one of the many examples of newsletters that have been successful on this platform. Established for free, in just six months it had 10,000 subscribers and 1.4 million dollars in revenues.

Substack also proved to be an advantageous opportunity for giving space to all those journalists who deal with niche issues and who, not finding a place in the world of newspapers, had for years resigned themselves to working as freelancers (3). Emily Atkin, an environmental journalist for the magazine New Republic, is a perfect example: after being let go, she created the newsletter Heated to talk about environment and climate change. Since landing on Substack, it has been highly successful: today Heated is the platform’s 11th most read newsletter and has approximately 2,500 subscribers, for a total of approximately 175,000 dollars in annual revenue.

Given the success of Substack, other similar information platforms are emerging: Patreon, Medium, and Ghost are some of the most recent alternatives.

These platforms are not only giving new life to the email channel, but have numerous advantages for the information world in general:

- they give space to sectoral and specific contents and themes

- they promote a meritocratic scenario in which the success of a writer and his or her newsletter is concretely and directly supported by readers

- they allow anyone with the ability and desire to express themselves to build their own following, speaking to a small and more interested audience of readers

- they allow full editorial freedom

- they have no advertising, only subscriptions

Newsletters land on social networks

The revival of newsletters is not limited to spaces like Substack. In fact, the news of Twitter’s acquisition of the newsletter management platform Revue is rather recent. The social network’s goal is to invest in the potential of newsletters and make the activation of the service available to its users. The intent is to attract writers, journalists, and publishing houses who want to expand their following thanks to the social network and capitalize on their texts, expanding the boundaries of tweets.

The difference between newspapers and newsletters

But what makes newsletters so popular and effective for the current historical moment? Compared to newspapers (printed and otherwise), these informative emails have the advantage of being more sectoral and of giving voice to more niche news and topics which hardly find space on other information channels. This aspect consequently makes the style and register of newsletters more specific, at times more technical, other times more colloquial and informal (or both, as in the case of the newsletter Robinhood Snacks, which often inserts funny GIFs and memes to “rejuvenate” and make the financial and economic sphere it focuses on less boring). Precisely for this reason, this type of information tool has a more marked identity and personality, which make each newsletter different from the other and which are the consequence of greater editorial freedom. Brevity and conciseness are the other great advantage that makes this channel the ideal information tool for the current scenario: today users are bombarded with an infinite amount of content and need quick solutions which let them optimize their time and attention that can be devoted to any source of information.

Conclusions

Newsletters are filling the information void left by the printed news crisis, revealing themselves as a tool capable of satisfying users on the one hand, thanks to the timeliness, brevity and ease of use representing the new needs of the post-digitization public, and writers themselves on the other hand, favoring greater editorial freedom and quality relationships with readers.